Image 1 of 4

Image 1 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Image 4 of 4

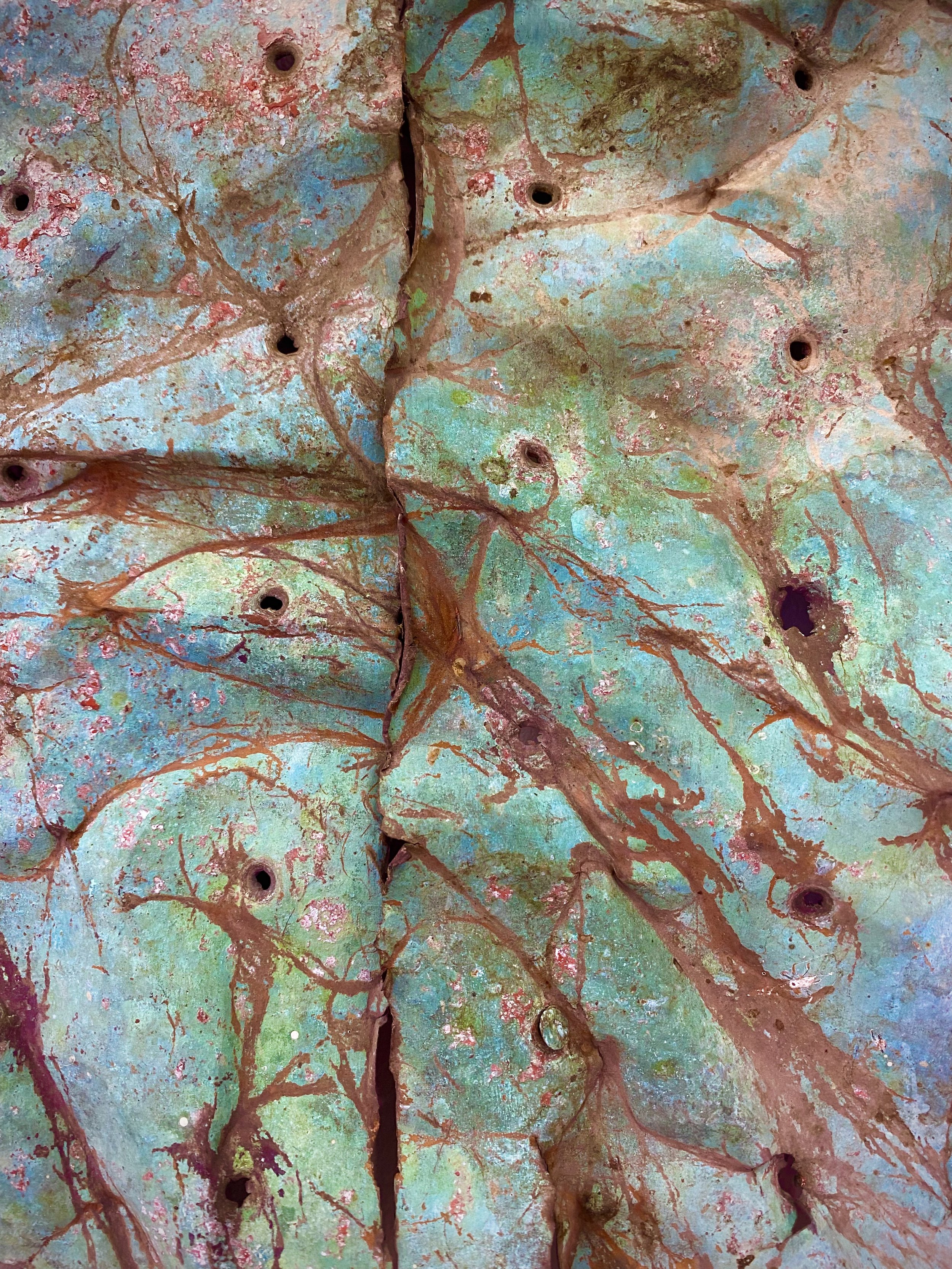

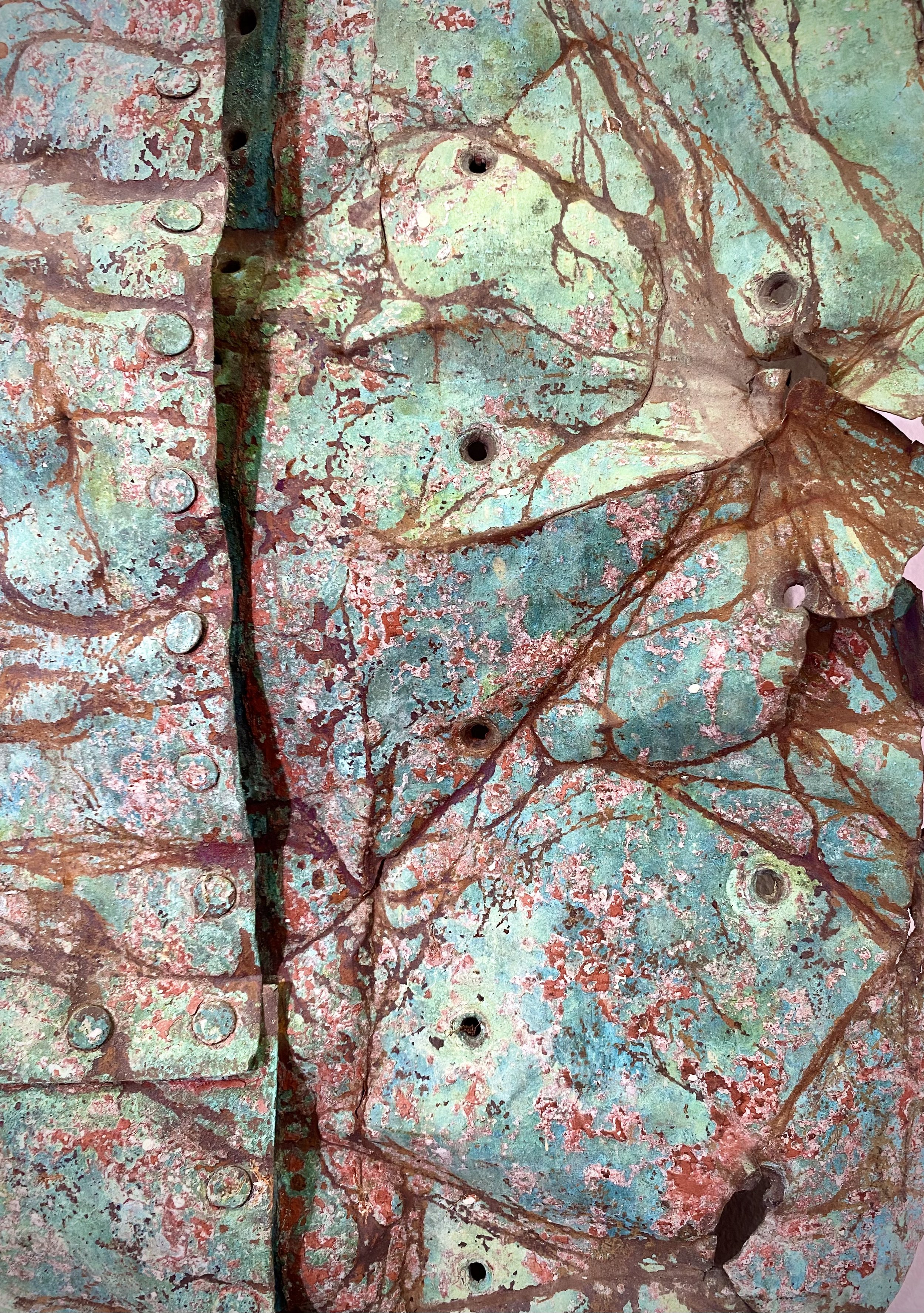

Ship's Copper

A lovely, crumpled, perforated section of “ships copper”, rich with verdigris. 19th century. 46” long. Can be displayed either vertically or horizontally.

Mariners in the Age of Sail faced many a serious problem while at sea, not the least of which was having the hulls of their ships devoured by shipworms. The “worms” (actually a type of mollusk) bored into the wooden hulls by the thousands, rendering them porous to the point of sinking. Furthermore, barnacles and seaweeds would festoon the hull on a long voyage, creating drag, and reducing a ship’s speed and maneuverability. What to do? Many solutions were explored over the millennia. Eventually, experimentation showed that copper was protective, and actually repelled clingy sea creatures. Voilà!

The British Navy began exploring the idea of sheathing its ships’ hulls with copper in the early 18th Century, but the Crown was dismayed by the cost. Not until 1761 was the decision was made to try the technique, on the 32-gun frigate HMS Alarm. It took the rebellion of the Americans in 1776 (compounded by the subsequent aggression of the French, Spanish, and Dutch) to justify the expense of copper-plating the entire British fleet. By the early 19th Century, many merchant ships had begun to use copper sheathing as well. Ships thus fitted-out were given reduced insurance premiums by Lloyd's of London, and the expression phrase "copper-bottomed" came to mean “low-risk” or “a good bet” in popular parlance.

By 1850, experiments with cheaper “anti-fouling” paints (most containing copper compounds) began to have some success, and soon copper-sheathing was a thing of the past. Anti-fouling paint continues to be used today, although concerns about harm to marine environments has caused it to be banned in some places.

“The vessel, though her masts be firm / Beneath her copper bears a worm.” From the poem “Though All The Fates,” by Henry David Thoreau.

A lovely, crumpled, perforated section of “ships copper”, rich with verdigris. 19th century. 46” long. Can be displayed either vertically or horizontally.

Mariners in the Age of Sail faced many a serious problem while at sea, not the least of which was having the hulls of their ships devoured by shipworms. The “worms” (actually a type of mollusk) bored into the wooden hulls by the thousands, rendering them porous to the point of sinking. Furthermore, barnacles and seaweeds would festoon the hull on a long voyage, creating drag, and reducing a ship’s speed and maneuverability. What to do? Many solutions were explored over the millennia. Eventually, experimentation showed that copper was protective, and actually repelled clingy sea creatures. Voilà!

The British Navy began exploring the idea of sheathing its ships’ hulls with copper in the early 18th Century, but the Crown was dismayed by the cost. Not until 1761 was the decision was made to try the technique, on the 32-gun frigate HMS Alarm. It took the rebellion of the Americans in 1776 (compounded by the subsequent aggression of the French, Spanish, and Dutch) to justify the expense of copper-plating the entire British fleet. By the early 19th Century, many merchant ships had begun to use copper sheathing as well. Ships thus fitted-out were given reduced insurance premiums by Lloyd's of London, and the expression phrase "copper-bottomed" came to mean “low-risk” or “a good bet” in popular parlance.

By 1850, experiments with cheaper “anti-fouling” paints (most containing copper compounds) began to have some success, and soon copper-sheathing was a thing of the past. Anti-fouling paint continues to be used today, although concerns about harm to marine environments has caused it to be banned in some places.

“The vessel, though her masts be firm / Beneath her copper bears a worm.” From the poem “Though All The Fates,” by Henry David Thoreau.